Epicentre of trafficking

Long before the earthquake hit last year, the districts around Kathmandu were already hotbeds of trafficking

Charimaya Tamang was just 16 when she was drugged, trafficked and sold into a brothel in India. She was rescued, and returned to Nepal in 1996.

Twenty years later, Nepal has introduced multiple measures, most importantly the 1998 National Plan of Action (NPA) to eliminate human trafficking, to allow the government to stop the scourge. But although reduced, trafficking is still rampant in Sindhupalchok, Nuwakot, Dhading and other satellite districts of Kathmandu.

Tamang founded Shakti Samuha along with 14 other trafficking survivors, and fought against trafficking. Their organisation won the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2013.

“Things have improved, girls are now relatively more aware and protected than they were in my time,” says Tamang who was honoured by the US government in 2011 with the TIP (Trafficking in Person) Report Hero Acting to End Modern Slavery Award.

However, new forms of trafficking are emerging, and the problem is now becoming much more complex than it was two decades ago. Whereas in the past trafficking rings sold young, uneducated and poor girls into Indian brothels, the destination has now shifted to the Gulf and even East African countries.

Shakti Samuha’s Executive Director Sunita Danuwar — herself a trafficking survivor — lists foreign employment, inter-country marriage and surrogacy as the new and most prevalent forms of trafficking. “Combating these new forms of trafficking is more difficult than fighting sex trafficking,” she says.

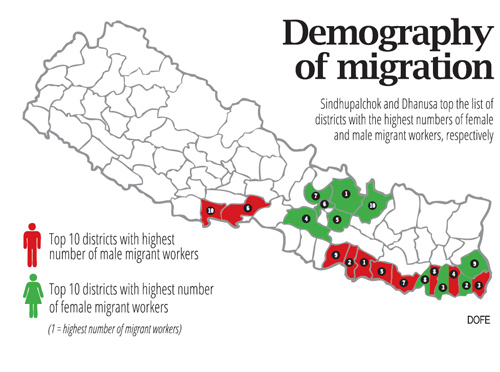

According to a 2014 report by the Labour Ministry, Sindhupalchok tops the list of districts with the most female migrant workers. Kavre, Makwanpur, Nuwakot and Dolakha trail close behind. These were also the districts worst hit by last year’s earthquake, which has deepened the crisis of human trafficking.

Two convicted traffickers, Sukhman Dong and Kaila BK, fled when the walls of the Sindhupalchok District Prison collapsed in the earthquake. They have not been arrested yet, and there are fears that they are back in business.

“After the earthquake, the girls from these districts are now more vulnerable because they have lost homes, and parents,” says Danuwar. Shakti Samuha has installed three more checkpoints in Sindhupalchok alone, to protect girls from traffickers.

While over 70 per cent of male migrant workers obtain labour permits through registered recruitment agencies, more than 60 per cent of female migrant workers do it individually. “This is alarming, women who obtain individual labour permits often end up being trafficked and exploited,” says Manju Gurung of the migrant welfare group, Paurakhi Nepal.

Ratna Kaji Bajracharya, a former Joint Secretary involved in formulating several anti-trafficking policies, says it is Kathmandu’s periphery where most women migrate from, because that had always been the hotbed of traditional trafficking. “It is like using the old slaves to catch new slaves,” he says. “The source districts of the trafficked girls are same, the modus operandi of trafficking is also the same, only the destination has changed.”

Most female migrant workers who obtain individual labour permits reach Arab countries as housemaids, and some of them are sexually exploited, not just by employers but also relatives and guests. Some of them also reach African countries as dance bar girls.

The precursors to trafficking can even be traced back to the Rana days, when young girls from Sindhupalchok, Kavre and Nuwakot used to be sent to the palaces in Kathmandu as concubines. But with the construction of highways connecting Nepal with India, traffickers began selling girls, most from Janajati communities, into Indian brothels.

An ethnic breakdown of the 336 trafficked girls rescued from India in 2014 and sheltered in the rescue and shelter agency, Maiti Nepal, revealed that 60 per cent of them were Janajati. “It is mostly Janajati girls who are sold into Indian brothels because they are easily manipulated, and they are also the ones trafficked to the Gulf and Africa,” says Bhagawati Nepal, a Sindhupalchok-based anti-trafficking activist.

The Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act 2007 defines trafficking not just as an act of forcing girls into prostitution, but also transporting people without their consent and forcing them to work. But the legislation does not clearly describe luring women into foreign jobs with false promises as an act of trafficking.

Sunita Nepal, of the anti-trafficking section of the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare, admits that the lack of clarity over whether tricking women or men into foreign jobs is an act of trafficking has made it difficult for the victims to get justice.

She says: “We are revising the Act, but this is not enough. There should be more awareness about trafficking itself.”

(Originally published in the Nepali Times, Nepal.)