Lahure laments: What songs say of the migrant culture

By the time I met my grandfather for the first and only time in 2000, his mental abilities were fast deteriorating. More often than not, he did not know where he was. He could not hear very well and he peed wherever he wanted. Yet, every now and then, he would regain his senses and peer at me and my sister with his one good eye and exclaim, “Oh, my granddaughters, my son’s daughters.” Then, within a few minutes, he would be sucked into his memories. One in particular stuck out: from the years he spent as a British army man in Malaysia – in the 1950s and 1960s, a time so far in the past, that his recounting entertained those watching him. But to him, he was a young soldier, standing once more in front of his commanding officer. He would recite over and over again, his rank, his name and his service number: Sergeant Nim Bahadur Pun. Service Number: 21134376. Sergeant Nim Bahadur Pun. Service Number: 21134376…

Aage aage topaiko gola

pachhi pachhi machine gun barara

cigarette nadeu ma bidi khanelai

maya nadeu ma hidi janelai

(Cannon balls in front me

Machine gunfire behind me

Don’t give me a cigarette – I am a bidi smoker

Don’t give your love to me – I am someone who leaves)

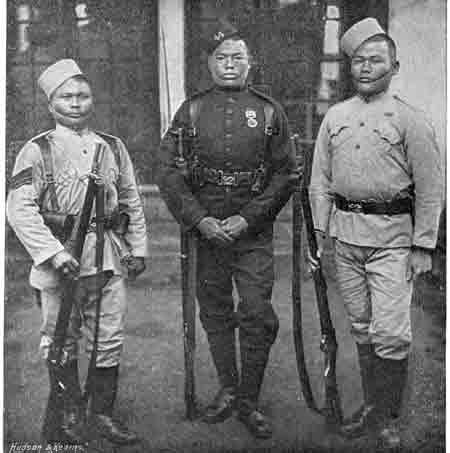

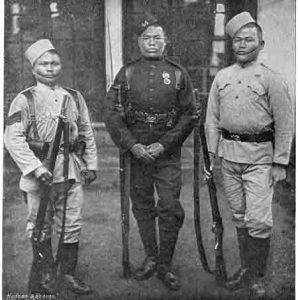

Photo : Wikimedia Commons / Hudson & Kearns

My grandfather had retired for almost a decade when Danny Denzongpa and Asha Bhosle sang this duet in the mid-1970s. But the song helps me think of my grandfather as a young, jocular, brave, flirtatious young man he might have been. Most ‘happy’ songs about lahures are similar. They portray ‘lahures’, a term that initially described Nepali soldiers serving in foreign armies, as the ‘lucky’ ones, characterised by bravery. These songs downplay the horrors of war and violence with an apparent insouciance that combines cannon fire with cigarettes; in the voice of soldiers who accept the reality that love might not be for them since they could be here dancing and singing today, and a casualty in a war tomorrow.

Over time, as the social and political milieu changed, so did the songs and, in doing so, the songs mapped the landscape of Nepali migration, in which actors change, but the pathos doesn’t. It is hard to tell when the first song about lahures was sung. The lahure culture began well before the Sugauli treaty with the British in 1816, an arrangement following which the colonial army began enlisting Nepalis. Nepalis have been migrating to India for seasonal work for centuries. Today, the songs about lahures have expanded to encompass the voice of the Nepali labourers, who began migrating to the Gulf countries and Malaysia in large numbers at the turn of the century. As these migrants became a part of the construction industry abroad, separation, loss and longing became a permanent part of the Nepali landscape. That pathos is reflected in the songs regardless of how gleeful they sound.

The ‘happy’ songs talk about the economic freedom that comes with being a lahure, about falling in love and about coming home after a long time away. But the upbeat music manages only to disguise the sadness that always accompanies these melodies. Then, there are ‘sad’ songs which do not mince words at all and hold a mirror to the harshness of a lahure’s life and of the people he leaves behind. These songs talk openly about death here and abroad, about poverty and about the pain of separation from the loved and the familiar. The third kind of songs – such as J B Tuhure’s Jaanna ma ta ni Gorkha bharti (I won’t enlist in the Gurkha army) – is against the lahure culture. These songs are often called ‘communist songs’. Left-political parties have always been against the lahure culture as it meant sacrificing their lives for foreigners. They are ‘patriotic’ in nature and believe toiling in Nepal would make it as prosperous as any of the destination countries.

Irrespective of the themes, however, songs about lahures and migrant workers make acute the absurdity of working abroad in a place which so often squashes dreams. Yet to believe in something else, to believe in sweating in Nepal, as some songs ask the lahures to do, would be equally futile.

Intu Mintu Londonma

Hamro baba paltanma

Schoolako paledai

Pahilo ghanti bajaideu

Tininininininini jhyaapa

(Intu, Mintu are all in London

My father is in a platoon

Security guard brother of our school

Please strike the first bell

Tininininininini gotcha)

~ A Nepali children song.

My uncles tell me that my grandfather fought with the British in the Malayan Emergency, which lasted for 12 years from 1948-1960. Two hundred and four British-Gurkhas died during the Emergency. My grandfather is no longer here to tell me the whole story. After years of battling with old age, he died in 2012 at the age of 87. But I am told he came straight to the hills of Baglung after retiring and loved talking about his days, and those of others, on the battlefield. He would recount mostly the horrors of the World Wars – in which more than 40,000 British Gurkhas died – even though he participated in none of the wars. In fact, the Second World War had just ended when he joined the army in 1946.

I wonder how he told these stories. Did he see the irony of fighting for a country Nepal had once fought? Did he try to compensate for that irony with a humorous and light-hearted tone? Did he minimise the implications of being a lahure by accentuating the stereotype?

Nineteen Fauntin yuddha ladda pako maile takma

Tinta dushman chhwattai kate maile risautheko jhokma

Yo manle rojechha eutalai, phul chadhai dhogchhu deutalai

Laidiunla maya jhyaammai

(I received an honour in the battle of 1914

I hacked three enemies in anger

My heart has chosen one. I offer a flower to the God

I will fall in love completely)

~ Takme Budo Nineteen Fauntin, a song by Wilson Bikram Rai

Or did he feel lucky that the soldier in the most classic song about lahures, Aamali sodhlin ni, did not represent him. That he did not perish in a far-off land, unbeknownst to his loved ones. That he did not need a letter with a red ribbon or a singer with a sarangi to carry home the news of his death.

Hey barai

dasi dhara po naroye aama

banche pathamla tasbirai khichera

kasto lekhidi bhabile

karma lila chhaina lau hajura

…

Batauliko bazaarma

Char paisako laha chhaina

Sirko swami sworge hunda

Ghara basnilai thaha chhaina

(Hey barai

Mother, don’t weep over me

If I live, I will send you a photo

Look what fate has in store for me

My karma is dark

…

In the markets of Batauli

There isn’t a stamp worth four paisa

The household head is dead

But no one at home knows)

~ Aamale Sodhlin Ni, a song by Jhalak Man Gandharva

But could he count himself lucky? Does a lahure ever count himself lucky? What does it mean to be lucky when the employing country takes advantage of the fact that a person is escaping poverty? Then, again, perhaps for a lahure, Nepal does not have borders. How can it not, though? Did my grandfather not know how lowly paid he was compared to British and Commonwealth soldiers? Did he realise that even the 2007 British court ruling barred him from receiving a pension equal to what his British counterpart get? Or like many other lahures, was he just grateful to have had a job and dismissed cries for equal rights with, ‘We come from a poor nation. We shouldn’t be too greedy. Politics is a game for the privileged. Nations and governments are ideas that a satisfied stomach churns. The pangs of an empty stomach are “simple enough.”’

Paiyaan gudan laagya, Bombai jaane relgadika paiyaan gudan laagya

aba chhutan laagya pahadka danga khola aba chhutan laagya

…

roidinya koi chhaina paradesh maranyako roidinya koi chhaina

(The wheels of the train are ready to roll on towards Bombay

The hills and mountains will soon recede

…

I have no one to cry for me, if I die, in this foreign land)

~ Paiyaan gudan laagya, a song by Bhojraj Bhatta

The social and political contexts have changed since Jhalak Man Gandharva’s song, Aamali sodhlin ni, was aired on Radio Nepal in mid-1960s. After nearly 200 years in service and multiple court battles, Nepalis who enlist now in the British army are treated, financially, as equals to the British in the British army. Since 2007, all serving British Gurkhas are entitled to equal pay and pension. Two years later in 2009, the UK government announced that British Gurkha soldiers who had served for four or more years in the army were allowed to settle permanently in the UK. These rulings still discriminate against those who served for less than four years and retired before 1997, when the Gurkha headquarter was shifted from Hong Kong to UK. Though the campaign for equality is still on, for the few who enlist now, the prospects are rosy.

Chhanchhanai bagne khahare khola

Aba ta chhoro kudne bho hola

Din bhari kheldo ho, malai nai khojdo ho

Sanjh pare pachhi aamalai sodhdo ho

Khoi baba bhanera

(The river that crashes against the rocks

My son might be able to run now

He probably plays all day, looks for me

When the evening falls, he must ask his mother

For me)

~ Asarai mahinama, a song by Chuden Dukpa

The irony is that everything a lahure or a migrant worker misses, everything that is romanticised in songs, is still a part of the reality that is forcing the migrant to go. If the person chooses to stay, the future is just as grim, if not grimmer. The hills and the green terraces do not sprout enough for everyone. The lover might leave for another. And the community, including the mother, will harass him for staying at home and earning little. The songs forget these harsh realities, especially the ones that beseech the migrant to stay. The migrant has no option but to pack up and leave for better days in the future, for a reunion made sweeter by the years lived apart, for a dream deferred, even if that dream threatens to come back in a box.

Bhantheu aama Nepalma dukha chha

Bideshma ta paisako rukha chha

Kalo badal nilo aakashma

Gayeu aama chadhera jahajma

Farkeu baakasma

(Mother, you used to say that there is sorrow in Nepal

That there is a tree of money in foreign lands

Black clouds in the blue sky

Mother, you left on a plane

Came back on a box)

~ Bhantheu Aama, a song from the film Pardeshi, sung by Usha Magar.

If my grandfather ever dreamt about the end of the lahure culture in exchange for better days ahead for his family, that dream is still being deferred. All of his four sons, except my dad, joined the Indian army. They are all retired now. The oldest came back to the village and to farming. Two stayed behind in India for the sake of their children and the youngest recently retired and is back in Baglung, planning to move to the city of Pokhara soon. My oldest aunt is married to a retired Indian lahure and the youngest to a Saudi Arabian one. “I have nothing against being a lahure. If there were opportunities here, we wouldn’t go, would we?” says my youngest uncle, who fought for the Indians in the Kargil war of 1999.

Lahureko relimai fashionnai ramro

Rato rumal relimai khukri bhireko

Kalo kot seto jange galbhandilai feri

Musmus haschhan churruka thuki tarunilai heri

(It’s the lahure’s fashion that is very good

A red handkerchief and carrying a khukuri

A black coat, white shorts and a muffler

He looks at the young girls and smiles)

~ Lahure Ko Relimai, a song by Master Mitrasen Thapa.

***

On the night of Laxmi Puja this Tihar, I heard from my half-brother for the first time in 15 years. The last time I had seen him was with my grandfather. We had travelled to my father’s village for Dashain and my half-brother was furious that we were there. We had become estranged after our father left his mother and married my mom and soon after died in a stampede. His mother married again and took him with her. As he grew up, his hatred for my mom grew too and as in any polygamous family, the overt quarrels they had were mostly over our father’s ancestral property.

On that night in Tihar, though, the animosity was gone. He sent a long message, saying he was sorry that circumstances forced us to be so far apart. He was sorry that none of us knew our father. But mostly, he was sorry that he could not become the brother he could have been. Then, he sent a picture of himself standing next to a tray full of offerings to goddess Laxmi, his hands clasped in front, his head wrapped in a black-and-white checkered keffiyeh headscarf. The Goddess of wealth had sent him to Abu Dhabi as a policeman. He wrote, “I feel happy today. Tomorrow, this heart will be sad again.”

The problem with the lahure culture (including labour migration) is that a lahure alone cannot create opportunities here in Nepal. All that he can do is try to improve his own circumstances, encourage others to do the same and unwittingly, given the situation the country is in, perpetuate the same cycle.

Janmeko gaun, janmeko thaun, janmeko dalan

Ka hunchha afno ghargaun jasto arkako aagan

Yo jyana yesai naphyala khera bideshko dhawaima

ladi ra jujhi khani ra khosri bachaunla gaawaima

Pasina bagai chharaunla biun danda ra pakhaima

mariechha bhane maraunla baru aamako kakhaima

hamilai jun papile die yo dukha bhuktana

Ti garibmara papilai masna gaun gharmai farkana

(The village, the place, the porch you were born in

Their yard will never be like yours

Don’t waste your life on a foreign land

We will dig and fight right here in our own village

We will sweat and plant seeds in our own fields

If we have to die, we will die in our mother’s lap

There are sinners who gave us this pain

To annihilate those murderers, come back to your village)

~ From a song Babale bhanthe ni aashish mero by Raamesh Shrestha, Manjul and Arim

What is the alternative to becoming a lahure? Is the reality here better than abroad? My half brother worked as a policeman in Nepal for 15 years before he left for the Gulf. One more year and he could have retired. But for him there was little value in retiring as a policeman in Nepal. He made much less than our uncles and two of our cousins in Malaysia and Dubai. He could have taken pride in serving his own country, but he knew how hollow that pride would be. That pride would not buy him a land and a house in Kathmandu. That pride would not send his two daughters to good schools. And neither would it help him escape the cycle of limitations. Nepal’s border is like a fence with painful realities on either side. The choice is between rotten apples and rotten oranges.

The songs talk about memories, about beautiful hills and terrace fields, about a lover waiting and a child growing up without a parent. They talk about the futility of working abroad, killing a stranger’s enemies. They evoke the brutality of this life; play with the sentiments of being a Nepali. They remind you of what you are missing. They say you will never become a British, Indian or an Abu Dhabi citizen. But they provide no solution, no better alternative.

(Originally published in the Himal Southasian, Nepal.)