Migrating from traditional roles

People move from one country to the other primarily for better economic opportunities. No doubt it is not an easy option to leave your family and head for a destination where you have to work like machines and go through excessive mental stress.

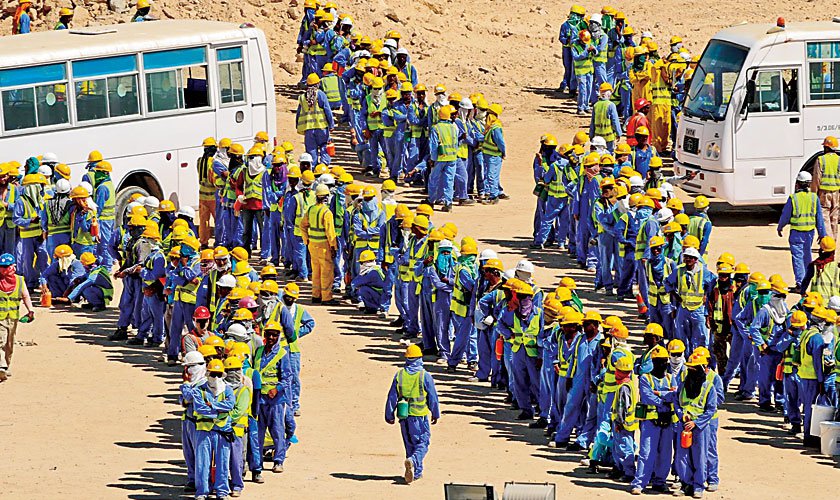

Official figures show that a total of 5.4 million Pakistani workers went overseas for employment from 2003 to 2015. Around 97 per cent of these went to Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) countries including Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Qatar. The contributions of these labour migrants are highlighted from time to time and the foreign remittances they send home are termed to be a lifeline for the country’s economy. During the year 2015-2016, Pakistani expatriates sent foreign remittances worth $19.9 billion which is not small a figure.

It is quite common that several migrant workers share rooms to cut this cost. Those with children of school-going age are even more pressed to keep their families back in Pakistan so that they can access affordable educational facilities.

Moreover, as approximately 90 per cent of temporary contractual workers from Pakistan are engaged abroad in semi to low-skilled employment, the options for women to find jobs there is negligible. These chances are further diminished as the government of Pakistan has imposed a ban on the recruitment of women as maids, domestic workers and caregivers for overseas job markets.

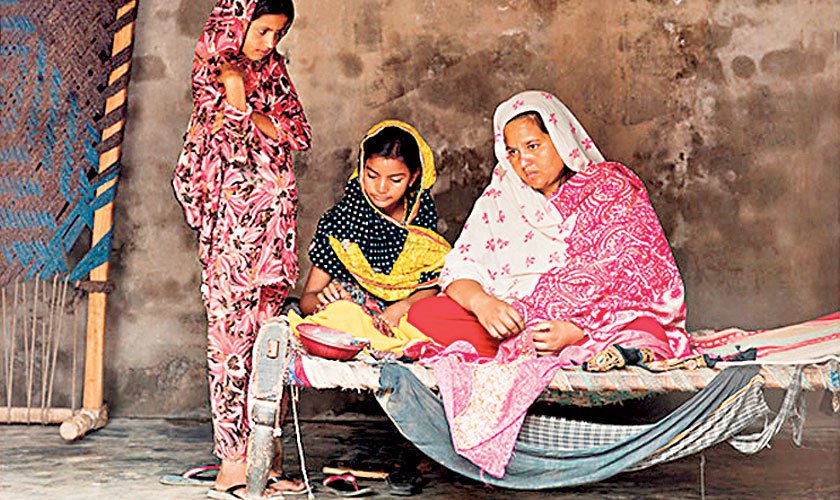

A number of studies have shown that labour migration of male family members brings major changes in the stereotypical roles of women in the society. This article is primarily focused on the role of women in this context and the challenges they face while trying to fill the gap created by the absence of their male family members who migrate. It also stresses on the fact that without the contribution of these women, male migrants cannot work abroad in peace.

According to Shahid Ghani, a career advisor based in Lahore, “Many women provide the initial expenses that are incurred on sending one abroad and buying job visa from the market. I know several cases where mothers or wives have even sold their jewellery or other assets or have even obtained loans to cover the initial cost of migration of their male members. And now they are regularly paying off these loans and managing the remittances sent to them from abroad very effectively,” says Ghani.

“The number of women who follow their husbands to the countries of their employment is not quite big, especially in the Gulf region, but those who do are called ‘trailing spouses’. These women mostly do not find work but give company to their husbands working abroad and take care of household chores. So, in both these cases the women’s role is integral and provides strength to the migrant workers struggling against all odds to make their lives comfortable,” adds Ghani.

In cases where remittances are managed by women, results have been exceptionally well and one reason for this is that they are very calculated when it comes to spending. Besides, the women have the experience of looking after day to day affairs and managing the monthly budgets from day one.

In the geographical areas of the country with concentration of international labour migrants’ families, it has been observed that more money is spent on healthcare, education, construction, to buy property, to purchase livestock etc. This affluence has also helped people hire labour for domestic and agricultural work, sparing family members including young boys and girls enough time to go to school more frequently. Previously, they were supposed to work at home and in the fields and assist their elders all the time.

Studies carried out on the impacts of remittances on the quality of life have also showed positive effects on the health of girls. The reason is that once the financial condition of the family is improved, the stress of work on these girls decreases, their nutritional intake increases and so does their awareness about health and hygiene due to education.

However, the picture is not always as rosy as it appears to be. In a joint family system, migrants may prefer to send the remittances to some other family member and not their wives. In such cases, the dependence of these women on the family heads increases and they may have to explain every time where they want to spend the money they are asking for.

While the expatriates living in the US, Europe, UK etc ultimately take their families there and settle there for good, the labour migrants in the Gulf region have to ultimately return home. That is why they concentrate on buying land in their home country and getting their houses constructed. With the rapid increase in the cost of living in destination countries, the migrant workers cannot fly back home as frequently as they could do in the past. This ultimately adds to the responsibilities of their wives who have to be vigilant and smart in their dealings.

Aneela, 43, is the wife of an expatriate Pakistani. She has recently purchased a residential plot in Rawalpindi, got all the documentation done and within a short span of time got construction work started there. She is dealing with the contractor as well as the building material provider and remains extra-cautious all the time. “People think it is easy to dodge a woman whose husband is away but I am proving everybody wrong. I talk to my husband on a regular basis and seek his advice before making any move. This has saved me from any mishaps. I know it is too tough to fulfil these responsibilities but I have no option,” she shares.

Aneela has to get the house constructed and then look for a match for her daughter who is of a marriageable age. In the absence of her husband, this responsibility also rests on her shoulders. The father of the girl will just come for a week to join the wedding ceremonies.

Fortunately, there has been a realization at the government level about the problems faced by expatriates’ families, especially the female members managing the affairs. Some time ago, it was pointed out in the Senate of Pakistan that expatriates send huge remittances but face issues such as illegal occupation of their properties back home by land mafia. It was also shared that there were hardly any forums for redressal of their complaints and that the Pakistani diplomatic missions were not much equipped to help them out.

It is a good development that the federal government and the different provincial governments are working in this direction and have taken certain measures as well. For example, Punjab province that has a major share in the international labour migrant workforce has established an Overseas Pakistanis Commission and has been given the task to attend to the problems and difficulties faced by families of overseas Pakistanis in their respective districts.

An official of the commission says, “The complaints are mostly about property disputes and housing societies, family disputes, criminal cases, telephone connection/problems, electricity connections/problems, natural gas connections/problems, water connections, travel agents and airlines related cases, employment requests/recommendations, financial matters/disputes, bank related matters etc. Because many a time women members have to pursue these cases on their own, so the chief minister of the province, Mian Shahbaz Sharif has instructed the commission to get these resolved on a priority basis. Furthermore, the police have been asked to be very strict with land grabbers and send the message that migrant workers’ properties are not an easy prey.”

Last but not least, there is a need to sensitise the society on the issues faced by women in migrants’ families and promote a culture where their roles are appreciated and given due respect.

(Originally published in The News Magazine, Pakistan.)