Over 5000 Indians Stranded As Kuwait’s Largest Construction Firm Falls

Migrant workers have been stuck in the Gulf country for over 18 months, without food, water or adequate shelter

“For the last 18 months, Embassy officials and ministers are coming and going. We hear the same words. We will be rescued soon, help is on the way, no need to worry… But now we are scared that we will die here without seeing our family.”

These were the words of a group of Indian workers who were left in the lurch by Kharafi National Company, one of the largest construction companies in Kuwait, which has shut down its operations partially, citing economic conditions due to oil price dip.

And as a result, around 1800 Indian workers, mainly from south Indian states, who have resigned from the company, are stranded without proper food, drinking water, accommodation, money and moreover travel documents.

Additionally, around 3614 Indian workers, mainly blue-collar workers, have filed complaints to get their unpaid salary and waiting in hope for the last few months.

Stranded Indians await help, MoS VK Singh addresses stranded migrants in Kuwait

Talking to The Lede, a senior official from the Indian Embassy in Kuwait, said that the amount is quite high and there is not much hope of company paying up. “We have calculated the pending salary for the workers as 8 million Kuwaiti Dinar (approximately Rs 169.38 crore). We are trying our best to get it for the workers,” the Embassy official told The Lede.

Last week, VK Singh, Minister of State for External Affairs, visited Kuwait and held talks with Kuwaiti ministers on resolving the workers’ issue. A few months ago, MJ Akbar, another Indian Minister of State for External Affairs, had also visited Kuwait and held talks to resolve the issue.

“After the repeated ministers’ visits from the Indian government, it seems that the Kuwait government is positive in resolving the issue,” the Embassy official added.

Meanwhile, the resigned and stranded workers said that it is getting harder by the day. “I came here with great hope. Worked for more than eight years. Now, the company is not paying us for the last one year. They are saying that they don’t have money. Top level management is ‘missing’ and the mid-level guys tell us that they are helpless,” Jose P, a worker from Kerala, told The Lede. “I have a family to take care of. My boy’s engineering education is stuck due to non-payment of fees. We are totally stuck here,” Jose added.

Jose cannot leave Kuwait because his passport is held back by the company. And even if he gets it back, he has to pay around (Rs 80,000) as fine for overstaying with an expired resident card. “The company failed to renew our resident cards and now, we are suffering for that. The salary is pending. Even if we get it, we have to pay back the loans we took to survive,” Jose added.

In fact, it is illegal for employers to hold the passports of employees, and this is clearly stated in ministry resolution number 143/A/2010 in Article 1: “It is prohibited for private sector employers and oil sector employers to hold travel documents of their employees.”

But in Kuwait, which follows the Kafala system – the bonded labour system – a majority of the workers have to surrender their passport at the time of arrival itself.

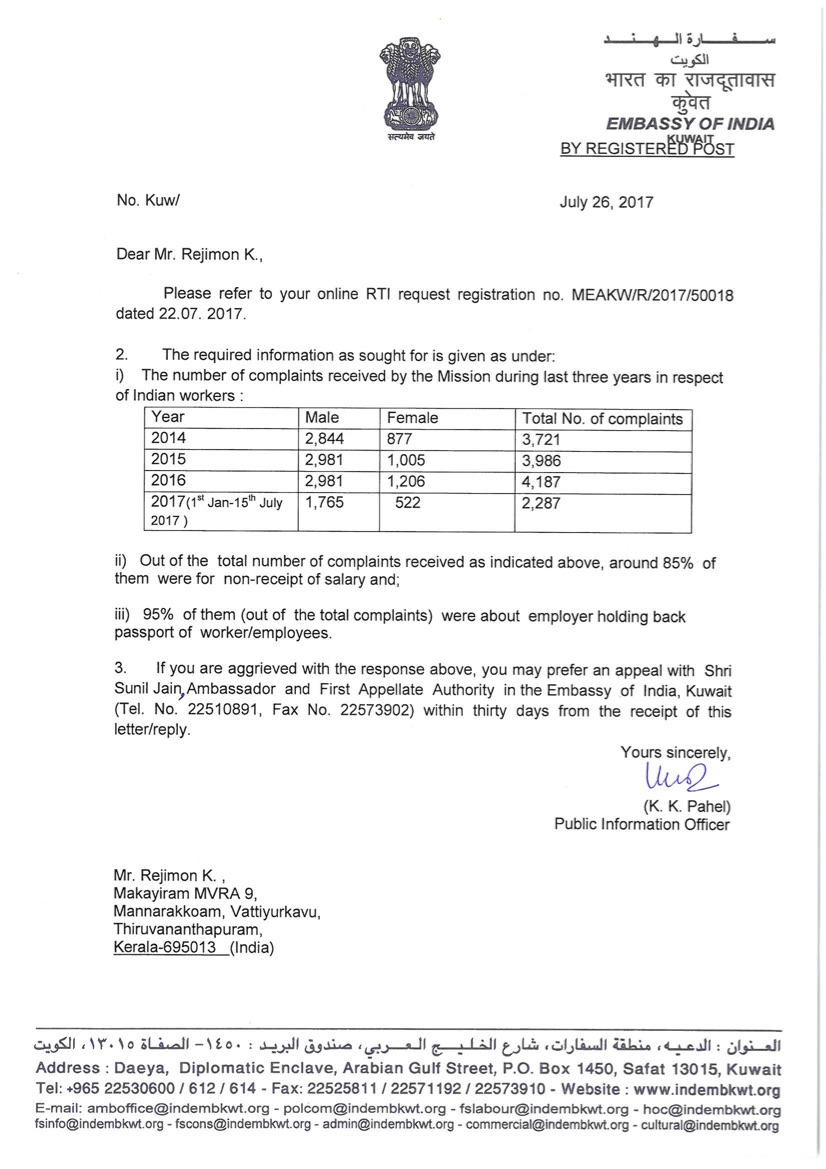

An RTI query filed by The Lede, has got a response from the Indian embassy in Kuwait – revealing that it has received 2287 complaints from the Indian workers. “Out of the total number of complaints received as indicated above, around 85 per cent of them were of non-receipt of salary and 95 per cent of them (out of the total complaints) were about employer holding back passport of workers,” stated the RTI reply.

While defining forced labour, the International Labour Organisation says that passport retention can be an indicator of forced labour. ILO says that forced labour, a violation of the basic human right to work in freedom and freely choose one’s work, is any work or service that is exacted from any person under the menace or threat of a penalty, and which the person has not entered into of his or her own free will.

According to ILO, two elements characterise forced or compulsory labour.

One is threat of penalty, which may consist in a penal sanction, such as the refusal to pay wages or forbidding a worker from travelling freely.

And the second one is work or service undertaken involuntarily, deciding whether work is performed voluntarily often involves looking at external and indirect pressures, such as the withholding worker‘s identity documents, including their passport.

In the case of the Kharafi company workers, it is clear that they have been subjected to forced labour as their passports are held back restricting their freedom of movement, as per ILO norms.

Rajesh S, a migrant worker from Tamil Nadu in the same company, said that as he is not well and wants to return immediately. He is going to give up his pending salary and pay the overstaying fine from his own pocket and go home.

“I have severe stomach pain. I need advanced treatment. So, I have decided to go home. And the only way to make it happen is spend money from my own pocket to pay the overstaying fines, get the passport and leave the country,” Rajesh added.

Around 30 workers from Mangaff camp were shifted to the main camp in Sulaibya and around 45 workers are holding a protest at the company’s headquarters. Shaheed Sayyed, an Indian social worker in Kuwait, said some of the workers are not physically well and some have emergencies back home.

“A few days ago, one worker’s father passed away and today (Jan 15, 2017) another similar case has happened. In both cases, the workers couldn’t go back,” she said. Shaheed, she added that after the Indian minister’s visit there are some positive developments. “We heard that the Kuwait government is ready to waive off overstaying fines and provide fresh visas for those who are willing to join new companies. Let it happen soon,” she added.

Meanwhile, Rafeek Ravuther, an Indian migrant rights activist in Kerala, said that waiving off fines and providing fresh visas is a welcome move. “But what about unpaid salaries? I know people in that company who have worked for more than 10 years. Think about their gratuity and other pending benefits. Will they be in a condition to find a new job or return empty handed?” Rafeek asked.

Kuwait and other Gulf countries are struggling financially following the dip in oil price since 2014.

Kuwait’s general budget has registered a KWD 1.94 billion ($6.43 billion) deficit in the first half of the financial year 2017-2018 which was concluded last September. “And when the country struggles, the first casualty is the migrant worker,” Rafeek added.

(The article is published as part of the author’s 2017-18 Panos South Asia Media Fellowship programme under the theme Forced Labour and Trafficking. The Panos fellowship is backed by International Labour Organisation (ILO), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and Ethical Journalism Network.)

(Originally published in the lede, India.)